I will never forget something that happened to me a few weeks ago.

I was part of a group of ecumenical church leaders who got to sing “Lift Every Voice and Sing” at Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama.[1] In 1954, Dexter Avenue Church was the first pastorate of then 26 year-old Martin Luther King, Jr. Under his leadership this church became a central meeting place for African-American community leaders planning and implementing the Montgomery Bus Boycott which sparked the modern Civil Rights Movement (1954-1968) with its sweeping social changes in American society.

The “Lift Every Voice and Sing” experience was like singing “He Lives” at the garden tomb in Jerusalem or “And Can It Be That I Should Gain” at Wesley’s Chapel, City Road, London. The confluence of past, present, and future in that place coupled with a diversity of voices raised together in this historic anthem reverberated to the deepest parts of me and is still resounding.

I came to this experience as part of the annual convocation of an ecumenical organization called Christian Churches Together. Their meeting, themed A Historic Moment of Lament, Transformation and Hope marked the quad-centennial of the forced transatlantic voyage of enslaved African peoples to Jamestown, Virginia. The gathering was appropriately set in Montgomery because of the city’s significant place in the America’s nineteenth-century slave trade and a century later it was a location where events critical in this nation’s struggles to end racial segregation, insure equal rights and opportunities for African Americans took place.

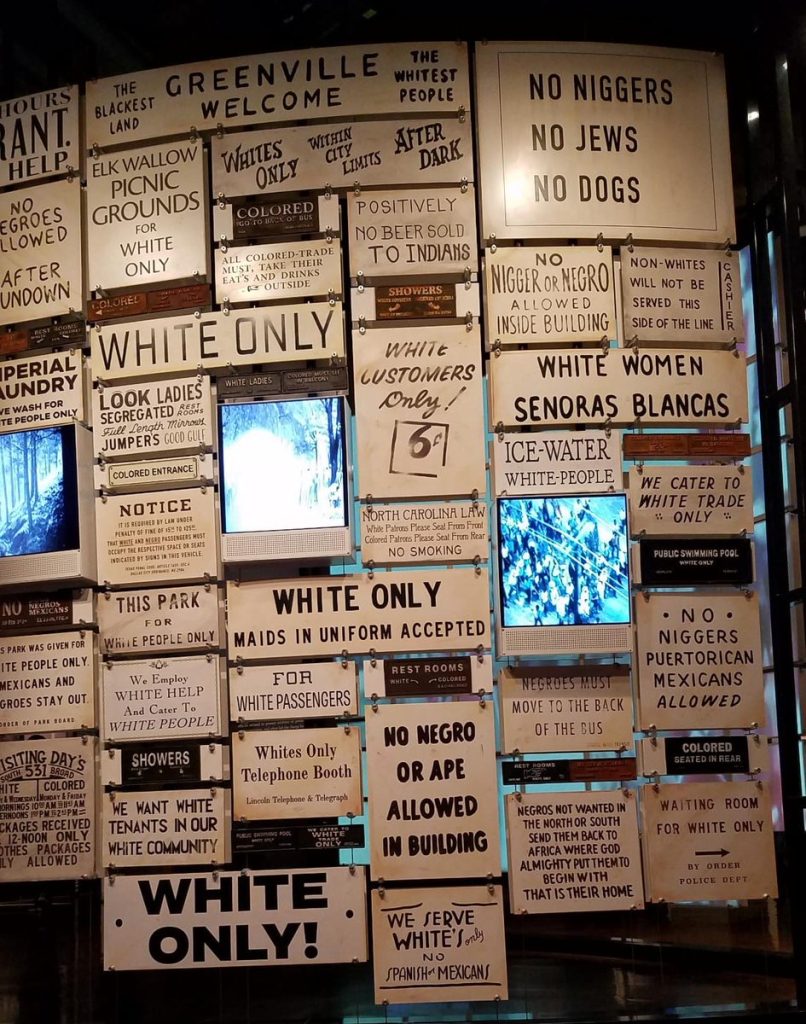

A day of pilgrimage began at the Equal Justice Initiative’s Legacy Museum. Exhibits traced the evolution of American enslavement of Africans and the racism it fostered from kidnappings in Africa, forced subjugation and servitude, Emancipation, Reconstruction, the Jim Crow era, lynching, legalized segregation, assumed racial inferiority and a new age of Jim Crow where mass incarceration of blacks—their guilt presumed and their person’s subjected to shoot-first policing—is slavery’s contemporary manifestation.

A slave pen replica, auction block, photographic timelines, audio testimonies, and life-sized sculptures dramatize slavery’s lethal legacy, none more graphically displayed than a collage of the actual signage used to explicitly message White Supremacy:

WHITES ONLY

NO NEGROES OR APES ALLOWED IN THIS BUILDING

NO NIGGERS, PUERTORICANS, MEXICANS

NIGGERS TO THE BACK OF THE BUS!

I was born in 1951. These signs and others like them were posted during my lifetime. What I was witnessing was not ancient history but part of my life and times.

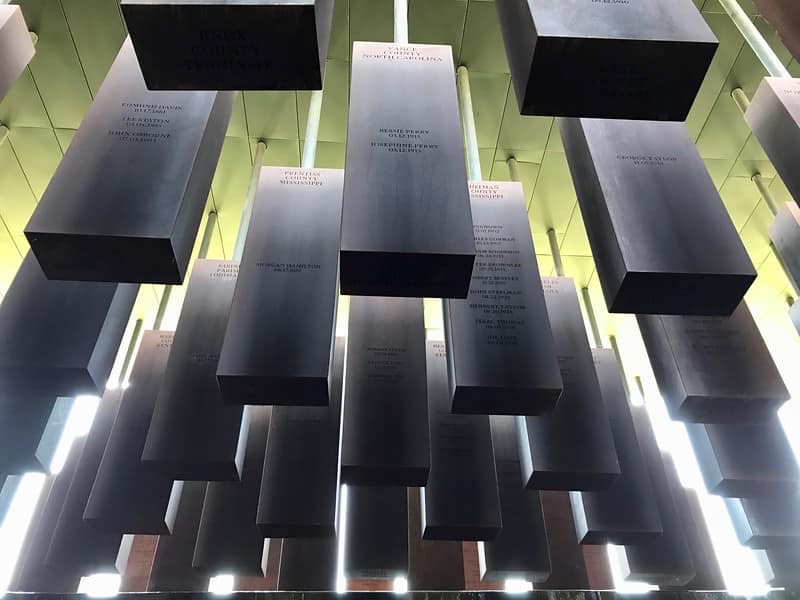

Still haunted by these reflections, we moved on to the central square at the Peace and Justice Center, a sculptural memorial to more than 4,000 blacks who were terrorized and murdered by lynching. Pilgrims walked among coffin-shaped hangings suspended from the shrine’s ceiling, each bearing the name of ones whose last gasps for breath came the end of a rope. The path among and through them lead to words on a wall, read to the sound of falling water:

For those hung and beaten.

For those shot, drowned and burned.

For the tortured and terrorized.

We will remember.

With hope because hopelessness is the enemy of justice.

With courage because peace requires bravery.

With persistence because justice is a constant struggle.

With faith because we shall overcome.

Our next stop was a marker remembering the Muskogee Nation, recognizing the original inhabitants displaced in Montgomery’s development as a white European settlement. Afterwards, we visited the site of the nineteenth-century slave market, ironically the location today of an ornate fountain bearing no witness to the place’s original grievous purpose, save a state historical society marker. We next traveled to the bus stop where Rosa Louise McCauley Parks boarded a bus and broke the law when she refused to relinquish her seat to a white rider. Our final stop was Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, in the shadow of the state capital where Governor George Wallace for many years was segregation’s enforcer.

This pilgrimage was the prelude to pilgrims singing—my unforgettable moment—chills-up-and-down-my-spine intoning, lament, transformation and hope:

Stony the road we trod, bitter the chastening rod,

felt in days when hope unborn had died;

yet with a steady beat did not our weary feet

come to the place for which our fathers sighed.[2]

The place for which our fathers sighed . . . . Kidnapped, sold to be serfs, shackled by an elaborate narrative of racial inferiority forming an American caste system. Terrorized with the threat of violence and lynching, presumption of guilt and dangerousness.

We have come over a way that with tears has been watered,

we have come treading a path thru the blood of the slaughtered,

out of the gloomy past, til we now stand at last

where the white gleam of our bright star is cast.[3]

“We have come over a way that with tears has been watered . . . .” “Segregated now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever,” were words spoken by a Methodist churchman. Segregation by customs and law. Old Jim Crow. New Jim Crow. Public education in America as segregated as before Brown vs. Board of Education. Mass incarceration. Police shooting young black men: Eric Garner, Michael Brown Jr., Labuan McDonald, Tamar Rice, Rumain Brisbane, Eric Harris, Walter Scott, Alton Sterling, Philando Castile, Terence Crutcher, Stephon Clark. Ferguson, Missouri; Charlottesville, Virginia; and Emmanuel AME Church Charleston, South Carolina.

God of our weary years, God of our silent tears,

thou who hast brought us thus far on the way;

thou who has by thy light led us into the light,

keep us forever in the path we pray.

Lest our feet stray from the places, our God, we have met thee

Lest our hearts drunk with the wine of the world we forget thee;

shadowed beneath thy hand may we forever stand

true to our God, true to our native land.[4]

Emotions stirred by this day in Montgomery linger. Tears still well up revisiting the anthem’s words and new images that bear their meaning in a lasting impact and a commitment to tell this story so that slavery’s first born child, racism, and its siblings white supremacy, fear and hate of the other will be exposed, confessed, processed to healing and reconciliation, uprooted and undone.

History, despite its wrenching pain, cannot be unlived,

but if faced with courage, need not be lived again. – Maya Angelou

To say my pilgrimage in Montgomery was a “good day” does not seem right. Perhaps it was a good day like Good Friday is “good.” Good as in the shocking, awesome and terrible goodness revealed on a certain Friday when the evils of the Lord’s trial, sentencing, mocking, scourging crucifixion, death and burial did not have the last word but instead burst forth in resurrection, new life and ways beyond the old ordering and boundaries. The moral arc of the universe bends to this story.

In the meantime there is still much work to be done. We must continue to tell painful truths and confess the wrongs of the past still lingering into the present and repent. Any hope for forgiveness without repentance is “cheap grace.”[5] We must process healing and reconciliation, abiding in one another as we move along the way. We must press onward to and through unfinished social change and transformation until racism and any exclusivism is completely uprooted and undone.

There is a song calling the cadence

Lift every voice and sing, till earth and heaven ring,

ring with the harmonies of liberty;

let our rejoicing rise high as the listening skies,

let it resound loud as the rolling sea.

Sing a song full of the faith that the dark past has taught us;

sing a song full of the hope that the present has brought us;

facing the rising sun of our new day begun,

let us march on til victory is won.[6]

Alfred T. Day III

[1] “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” is often referred to as the Black National Anthem. The song, first a poem, was written by James Weldon Johnson (1871-1938) and set to music by Johnson’s brother John Rosamond Johnson. It was written for exercises marking Abraham Lincoln’s birthday in 1900 and performed on that occasion by a choir of 500 black school children. It appears in The United Methodist Hymnal (No. 519) and has been sung for more than a century powerfully voicing a cry for liberation and affirmation for African-American people.

[2] “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” (No. 419, vs.2) in The United Methodist Hymnal (Nashville: United Methodist Publishing House, 1989).

[3] Ibid.

[4] “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” (No. 419, vs.3) in The United Methodist Hymnal (Nashville: United Methodist Publishing House, 1989).

[5] “Cheap grace” is an expression used by German theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer in his classic The Cost of Discipleship (1937). Bonhoeffer defines “cheap grace” as preaching “forgiveness without requiring repentance, baptism without church discipline, and Communion without confession… Cheap grace is grace without discipleship, grace without the cross, grace without Jesus Christ, living and incarnate.”

[6] “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” (No. 419, vs.1) in The United Methodist Hymnal (Nashville: United Methodist Publishing House, 1989).