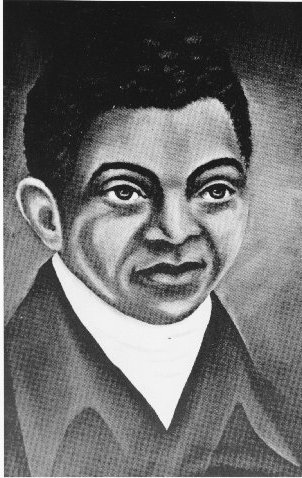

An African American Who Gave A Beat To Methodist Preaching

By John G. McEllhenney

Revised by Bishop Forrest C. Stith

No recording devices trapped the cadences and power of “Black Harry” Hosier’s preaching. But we may conjecture that given his African American heritage, his words poured out rhythmically and with a range of volume. This rhetoric, combined with a keen mind and outstanding communication skills, enabled the biblical truths he proclaimed to pulverize the stony hearts of his listeners.

“I really believe he is one of the best preachers in the world,” was the opinion of Thomas Coke, who, along with Francis Asbury, was one of American Methodism’s first two bishops. “There is such an amazing power attends his preaching, though he cannot read; and he is one of the humblest creatures I ever saw.”

In spite of such accolades, even the bare facts of Hosier’s life elude historians, who must therefore sprinkle probabilities throughout their narratives. Born about 1750, perhaps as a plantation slave, maybe in North Carolina, he experienced Christian conversion at some point and became Asbury’s traveling companion. Soon he began to exhort after the sermon, urging the listeners to apply the preacher’s words to their lives. Later, he was the principal speaker at services.

He and Richard Allen were the two non-voting African American representatives at the 1784 Christmas Conference, which officially organized American Methodism. He died, one authority says, “happy in the Lord” about 1806. Another specifies that his funeral was May 18, 1806, with burial in Philadelphia.

What transcends the biographical probabilities is the impression “Black Harry” made on the minds and hearts of those who heard him. Henry Boehm and Freeborn Garrettson, both ordained Methodist ministers, provide ear-witness accounts.

Boehm writes: “Harry was very black, an African of the Africans. He was so illiterate he could not read a word. He would repeat the hymn as if reading it, and quote his text with great accuracy. His voice was musical, and his tongue as the pen of a ready writer. He was unboundedly popular, and many would rather hear him than the bishops.”

Garrettson’s narrative helps us place Hosier within America’s race-conscious culture. Garrettson, following his conversion, found himself dejected. Then one Sunday as he led family prayers, a thought penetrated his melancholy gloom: “It is not right for you to keep your fellow creatures in bondage.” Whereupon he told his slaves they were free. Later, Hosier, a former slave, and Garrettson, a former owner of slaves, ministered together.

Traveling around the Delmarva Peninsula, Garrettson reports: Sunday, March 7, 1784—“Harry met me, and preached after I ended;” the next day—“as there was a degree of persecution against Harry I thought it expedient to leave him behind.” Six years later, 1790, on his way to Boston, Garrettson records: “The people of this circuit are amazingly fond of hearing Harry.”

Harry Hosier transcended the racial consciousness of his day. His famous sermon, “Barren Fig Tree,” (Adams Chapel, Fairfax County, Virginia), was the first sermon preached by a Negro in America. Likewise his sermon in Chapeltown, Delaware, 1784, was the first sermon preached by a Negro to a white congregation.

Garrettson writes that in Providence, Rhode Island, “Harry preached in the meeting house to more than one thousand people;” on another occasion, “Harry preached after me with much applause.”

Hosier illustrates the point made by a late twentieth-century scholar, who declares that American Methodism “relied much less on the written word than on that which was spoken Methodist preachers…were remembered first of all for their preaching and for the spontaneous verbal responses of their congregations—the shouts, the groans, the sobs of persons brought together to express their most interior and private thoughts.”

PDF of formatted bulletin insert