Francis Asbury (1745-1816), the first bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church, is the source of the episcopacy in Methodism. It was through the episcopacy, the traveling episcopacy, that Asbury was able to hold together the quickly growing and expanding church in the new country. Asbury’s leadership and personal style was germane to the development of this office. But it was more than just his personal charisma the created the office. If the office was founded on Asbury then we could expect it to go away after his death. There were cases in England, for example, of strong presidents vying for leadership against the conference, but once the person left that office, the status quo quickly returned. It was Asbury that created the office, but the office also filled a need for the young church that enabled its growth and development over the next century.

The beginning of episcopacy lays in the actions of John Wesley. To this day it is unclear if Wesley wanted to create an episcopacy or had something else in mind. But it was through his actions that episcopacy came into existence and the first basic understanding of episcopacy: a Bishop is an elder with administrative and leadership functions.

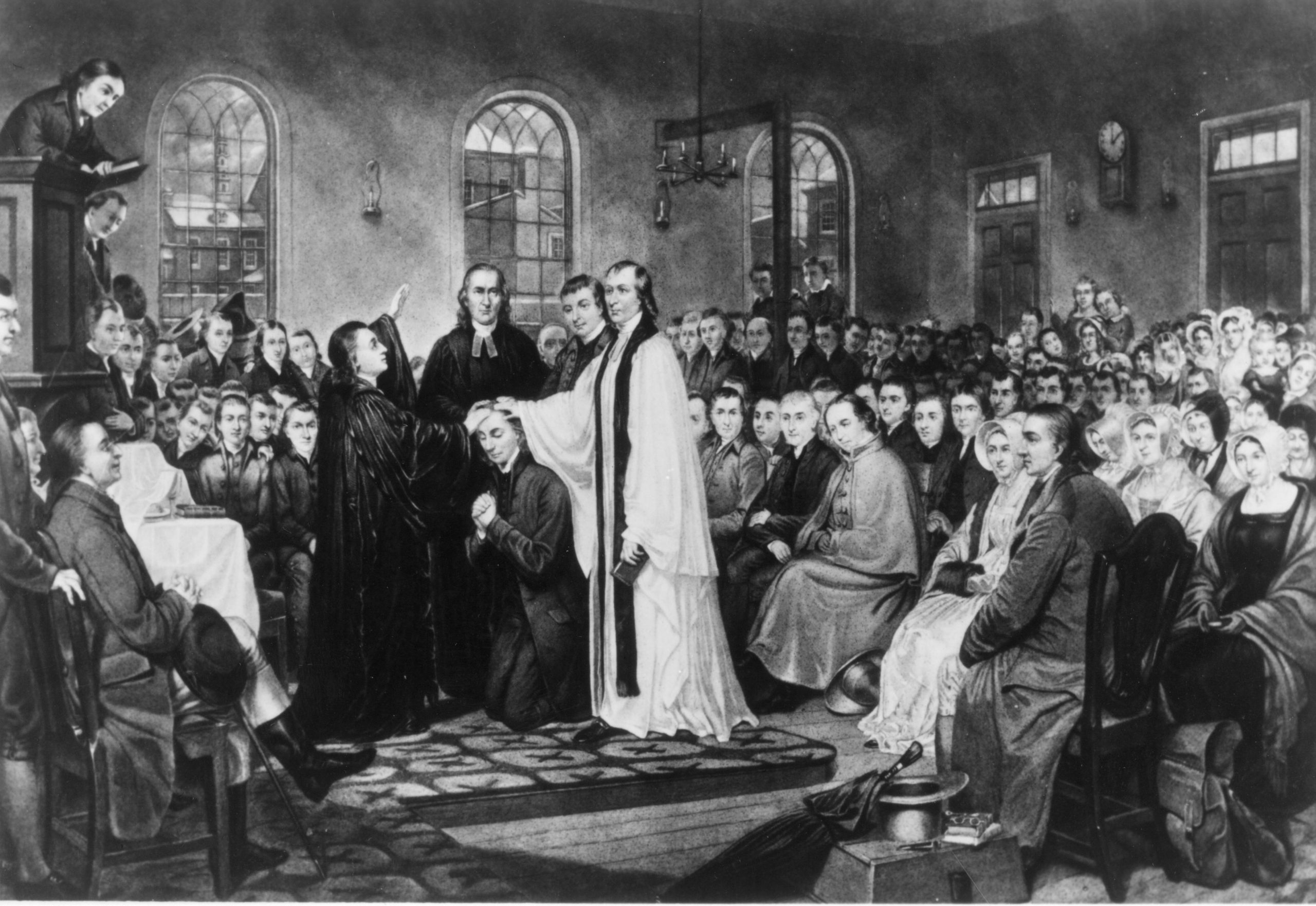

The next element of the episcopacy comes at the Christmas Conference where the church was formed and Asbury required that he be elected by the Conference. Coke had been assigned as ‘bishop’ by Wesley and Asbury had also been assigned the same status. The importance that Asbury attached to the election has become mythic in the history of American Methodism. The example and precedent has been understood by each generation within its own horizon.

Just as Wesley probably didn’t give much thought to all the implications of his actions ordaining and setting aside others (after all it was something that needed to be done) and so was shocked by some of the ways his actions played out, so too did Asbury’s demand for election. Some have interpreted it as a tip of the hat to American egalitarianism, while others have seen it as an affirmation of Asbury’s program (vote for me if you are ready to follow me) . We may never really know what was in Asbury’s mind. We do know that the precedent required the election of our bishops.

Asbury and Coke also set the example for bishops to be commentators on the church’s actions. At one end they annotated the Discipline so as to explain or amplify its meaning. And they also visited President Washington, giving him greetings from the new denomination and leaving a petition for the abolition of slavery.

Asbury’s yearly travels not only set the tone for the pastors; they traveled because he traveled, it also set the example for future bishops throughout the rest of the 19th century. The various conferences, even though they were no well-defined geographic areas – diocesan in effect – were treated much more like ‘stations’ on a circuit. As Asbury aged and other bishops came on, Whatcoat in 1800, M’Kendree 1808, each was elected. M’Kendree added the cabinet as an advisory body on appointments, over Asbury’s objections.

But the most lasting concept was the two centers of authority; the General Conference and the episcopacy. The two centers were always in tension, even when they worked together. Over time there were those who favored a strong episcopal leadership and there were others who favored leadership from the General Conference. Together the two centers would push and pull the denomination in new and unexpected directions.